Basics of Private Equity Fund Mechanics Explained for Beginners

Basics of Private Equity Fund Mechanics Explained for Beginners

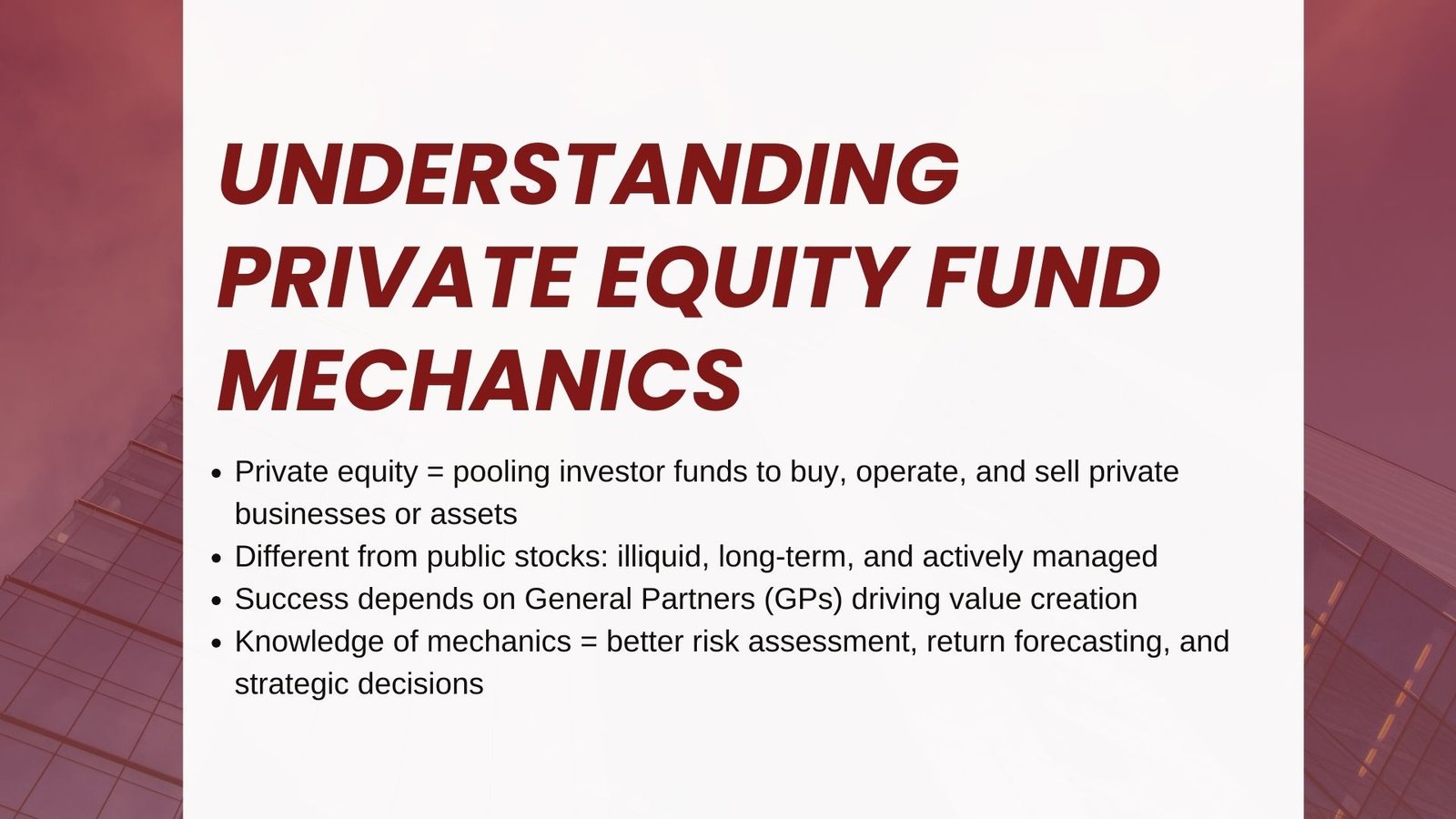

A leading concept in alternate investments is that of creating private equity, which entails pooling of funds contributed by investors to purchase, operate and finally sell investments in privately owned companies or properties. In comparison with publicly traded stocks, private equity is illiquid, a long-term, active investment, and it depends on the general partners of the fund to add value. Gaining insight into the workings of a private equity fund is crucial to the investors as well as those who are in the profession.

The operational set up, financial structures and the life stage processes determine capital flows within the fund, creation of returns and mitigation of risk. This is why professionals often seek Fundraising strategy and process training Singapore and Hands-on private equity training Singapore to strengthen their expertise in this area. A typical structure of a private equity fund is a limited partnership where general partners manage the investments and the limited partners are those that invest the majority of the pool of funds.

The mechanics entail complex contract arrangements on capital commitments, investments mandates, fees and share of profits. All these are determinants of the manner, in which the fund should be run between its inception and its closure. To funds managers, being informed on such mechanisms is the key to achieving performance benchmarks and staying within the legal frameworks. As an investor, knowledge on these factors aids in assessing the possible returns and risks as well as the interests congruence with the managers.

Fund Structure and Roles of Key Participants

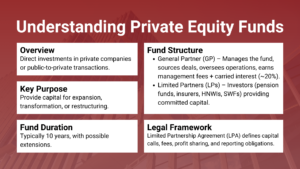

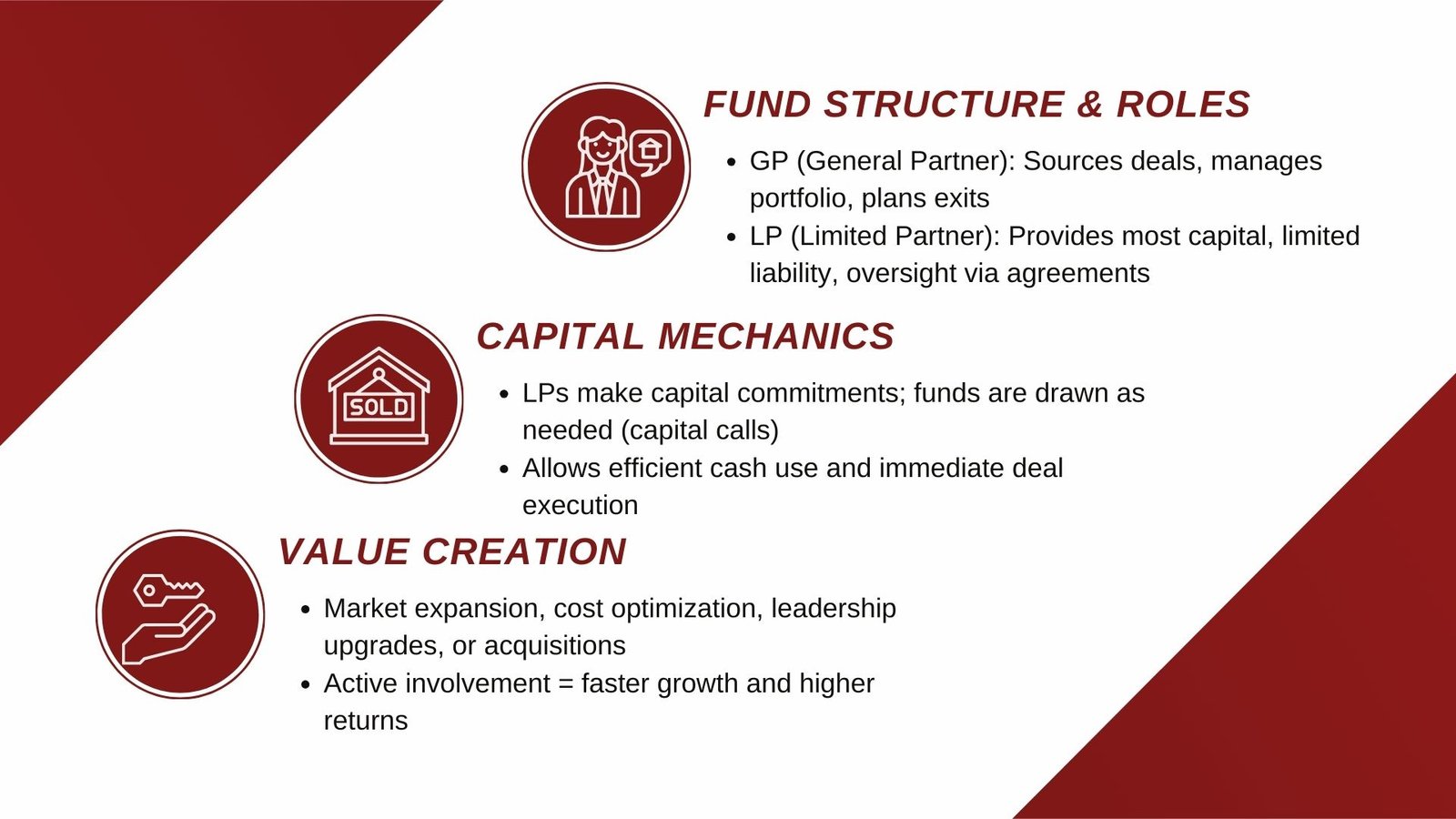

A primary stakeholder of a private equity fund is it s legal and operational structure, usually established as a limited partnership or some other vehicle that provides the balance between flexible operations, and legal protection. The managing body is known as the general partner (GP), whose role is to find deals, perform due diligence, negotiate acquisitions and run the portfolio companies. The GP also dictates when and how exits take place and they are the main determinants of the fund returns.

The investors making the capital commitment to the fund are limited partners (LPs), and may be institutional investors- pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, endowments or high-net-worth individuals. LPs contribute most of the capital with limited liability and do not participate in day to day decision-making. Rather they impose their influence by the terms negotiated in the limited partnership agreement (LPA) that regulates capital calls, reporting requirements, investment parameters, and other working practices.

The LPA also states the term of the fund, usually ten years with allowances of extension. The first years are devoted to the deployment of capital and followed by holding period, when the portfolio companies are actively serving and enhanced, and then the final stage, harvesting, when the investments are exited and capital is returned to the LPs. Such a governance system also guarantees consistency between GPs and LPs, as well as a government system with operational power and responsibility.

Capital Commitments, Calls, and Deployment

The capital commitment model is one of the defining features of the mechanics of a private equity fund. As opposed to mutual funds, where the investors invest all their capital in advance, in the case of a private equity fund, investment and drawing down takes place as per a commitment and drawdown basis. Initially, the LP is obligated to provide a predetermined number to the fund which may be drawn down by the GP during the investment term, usually the first three to five years of the fund.

Capital calls are made when the GP finds an investment opportunity all the time or requires capital to make follow-on investments, administrative charges or even other expenses that have been approved. LPs have binding mandates to avail the capital over characterized notice period, mostly 10 to 15 business days. Such a system reduces wasting capital, and it enables LPs to leave uncalled commitments in other investments until they are asked to fund them, and it also grants the GP available liquidity to make deals immediately.

The investment strategy given in the LPA is used in deploying the capital. The investment is typically done in a portfolio company that has growth potential, has some form of operational inefficiency that can be addressed by the capital provided, or that has potentially strategic value that can be unlocked by active management. The GP can also hold back a part of invested capital to make follow-on investments in current portfolio positions, thereby help them expand, make acquisitions or pursue restructuring programs. Capital deployment requires judicious spending of time and effort between speed and how well due diligence is conducted to meet the targets on fund returns.

Value Creation and Portfolio Management

The core concepts of private equity are value creation, which is more than the pumping in of capital. After making an investment, the GP closely monitors the portfolio company in order to improve its performance in terms of both its operations and finances. This may include strategic measures including: entering in new markets, supply chain optimisation, cost efficiency, management team strength or new products and services development.

It is quite common to find that the private equity firms commonly infuse expertise, networks, governance discipline about a particular industry into the portfolio companies aiding them to grow and attain profits sooner as compared to when they would have developed independently. Financial engineering is also an extra factor in leveraged buyouts (LBOs) whereby the debt increases the equity returns. In such market situations of volatility, the GP has to reconcile leverage advantages with the threat of financial hardship.

Documentation of monitoring on the portfolio includes careful tracking of the performance, regular board sessions, and close interaction with the executives of the company. The GP can also hire the services of a consultant, a professional in the field, or even an interim manager to meet a certain challenge. The objective is to amplify the enterprise value substantially throughout the investment horizon which also has an average of three to seven years per organization, and establishes the company in a way that will exit with a profitable operation.

Exit Strategies and Distribution Waterfalls

The most important part is exciting investments in which a private equity fund harvests the value it has created and returns the returns to LPs. The avenues most frequently used as an exit strategy are initial public offerings (IPOs) , strategic sale to industry players, secondary buyout to other private equity partners or retap up and maintenance of capital. The exits are based on the market conditions, the performance of the company, and the maturity of the funds where the GP will want to ensure that maximum returns are achieved and at the same time maintain risk trade off.

The distribution of profits has a structure referred to as the distribution waterfall and this is what defines the method of distribution of proceeds between the LPs and the GP. The payout order is normally capital contributions to LPs, traditional preferred return or a hurdle rate that gives the minimum return to the LPs per year before GP can participate in the share of profits. After the hurdle is overcome, the GP obtains a proportion of profits-usually 20 percent, or carried interest-and the rest goes to the LPs.

There are differences in waterfall structures as there are European-style waterfalls, and then American-style waterfalls where profit distribution can take place on a deal by deal basis after all capital invested is repaid. Investors and fund managers pay particular attention to the understanding of these structures since their direct implications are related to cash flows, incentives, and the alignment of interests.

Fee Structures and Incentive Alignment

The fee structure defines the economics of a private equity fund, and it rewards the GP for management and gives it an incentive to generate performance-related fees. The typical model is the “2 and 20” structure: 2 percent a year in management fee based on committed or invested capital and 20 percent of profit over the hurdle rate in the form of carried interest. Operating expenses, salaries, due diligence costs, etc, are covered by management fees, in addition to various administrative functions.

The main focus on the kind of performance-based payment to the GP is carried interest which puts their incentives into connection with those of the LPs. Nonetheless, the fee arrangements can be quite different on the basis of fund size, strategy and market conditions. Certain funds will allow lower management fees depending on the size of commitment or longer term investment period whereas some could also offer graduated carry interest to incentivize incredible performance.

Investors and regulators have directed more focus on fee structures and detail on costs incurred, transaction commissions and offsets used. Economic incentives are clear to facilitate the focus of the GP to create good returns to the fund, but not just to increase the assets under management.

Conclusion: Mastering Fund Mechanics for Success

The art of a private Equity fund involves an intricate multi-factor complex enveloping legal wrapping, financial resources, proactive portfolio involvement, exit strategies and the best economic incentives. Learning these mechanics is central to successful execution of investment strategies by general partners, as well as the establishment of investor confidence and the provision of competitive returns. To a limited partner, greater knowledge on how funds are run will help them make better investment decisions, enhance their ability to assume risk and have better expectations on cash flow projections and performance.

Just as private equity moves forward as the regulations change, dynamics in the markets, and demands of investors, it is necessary that managers and investors adjust their strategies in relation to fund mechanics. Changing the situation is an improved level of transparency and new fee structures, as well as a higher level of portfolio management. After all, the making of a successful private equity fund is pegged on the capability to develop concurring interests among various participants including the staff, deployment of capital skillfully, development of long-term, and long-sustaining value within portfolio firms, and the successful and in-time exits.